The Fifth Report on Internet Quality in Iran: From 93% VPN Usage Among Iranian Youth to the Rise of Starlink Consumption

1404/05/12 (August 3, 2025)

The fifth report on the quality of internet in Iran has been published by the Internet and Infrastructure Commission of the Tehran Electronic Commerce Association. Drawing on technical data, national surveys, and expert analysis, the report examines the current state of internet quality in the country and reviews trends affecting user experience, businesses, and network infrastructure.

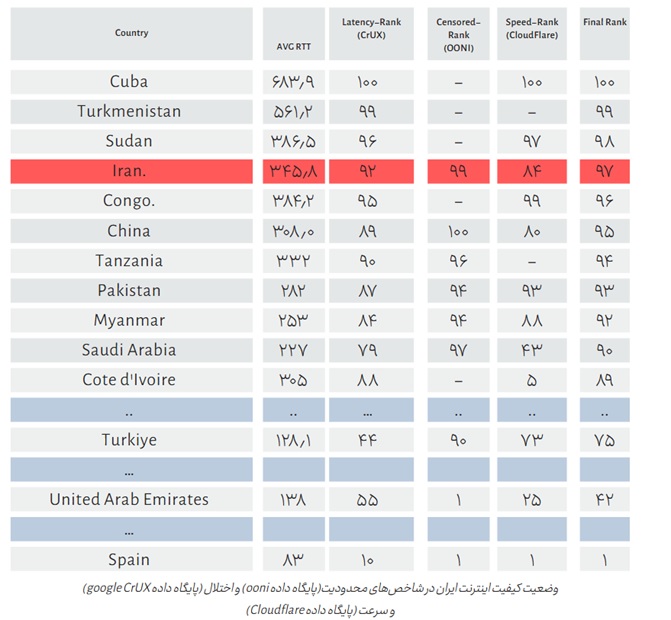

Iran Ranks Lowest in Internet Quality Among the Top 100 GDP Countries

If we assess Iran’s internet quality without considering the extraordinary conditions during the “Israeli attack on Iran,” there is no significant difference compared to the fourth report (ranked 95th out of 100 countries). Internet user experience in Iran can still be described by three key characteristics: slow (84/100), highly disrupted (92/100), and heavily restricted (99/100). Overall, based on the average ranking of these three indicators, Iran ranks 97th out of 100 in internet quality.

Methodology

As in previous reports, we selected internet quality indicators from diverse and reliable data sources and used Iran’s average performance in each as the basis for final ranking.

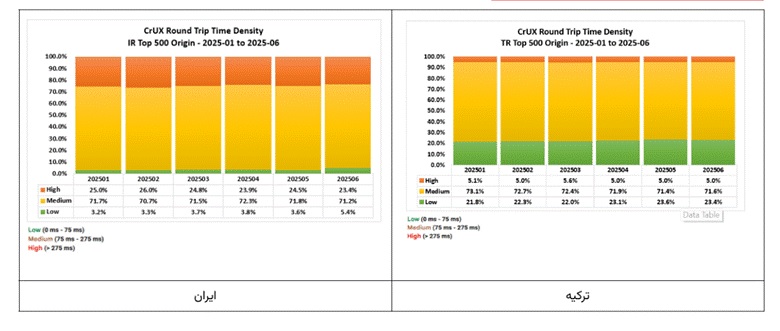

- Latency (which also reflects aspects of disruption) was measured using Google CRUX data.

- Restrictions were assessed using the OONI database.

- Speed was measured based on Cloudflare Radar.

Among countries that had rankings across all three indicators, Iran ranked 97th out of 100, making it the country with the worst internet quality in this group.

Although hearing for the fifth time that “Iran is at the bottom of internet quality rankings” may no longer be surprising, poor internet quality should not become normalized for users. Unlike sanctions-related factors, the causes of Iran’s poor internet quality are more controllable. With rational decision-making, these limitations could be removed quickly.

Simply by changing domestic policies—such as lifting filtering on social networks and practical or educational websites—and by improving network conditions (eliminating imposed disruptions under the pretext of combating VPNs), Iran could, even with its existing national resources, significantly improve the experience of digital businesses and citizens, and restore public trust.

Statement by 100 Iranian Startups: End Internet Restrictions

More than 100 technology companies active in Iran’s ICT sector have emphasized this point in a joint statement. In the statement, they call for:

- Lifting filters on social networks and widely used educational and skills-based websites,

- Increasing international bandwidth speed and capacity, and

- Removing restrictions on emerging protocols such as HTTP/6 and IPv6,

as core demands for achieving free and high-speed internet for all Iranians.

(This statement was issued at the invitation of the Internet and Infrastructure Commission and is included in full, along with the names of the signatory startups, in the fifth report.)

Moreover, extensive restrictions have not brought any benefit to the country. On the contrary, they have encouraged the widespread use of unsafe VPNs. This has imposed additional costs on households, polluted the network, and—most importantly—led to serious security incidents.

Previously, in the fourth report, we highlighted Israel’s exploitation of the high demand for VPNs in Iran. In Tir 1404 (July 2025), the Science and Progress Group of Iranian news agencies also published an in-depth report on the security and network risks posed by VPN usage.

In the introduction to that report, regarding the policy of internet shutdowns as a tool to protect citizens, the authors state:

“As network and internet professionals, we are interested in better understanding decision-making processes related to national cybersecurity. Given the importance of free internet access for citizens, several technical questions arise: In situations involving security threats, what technical criteria are used to assess the necessity of restricting internet access? Are there alternative methods to protect national cyber infrastructure while still ensuring citizens’ access to the internet? How can a balance be struck between security needs and citizens’ digital rights? What decision-making and risk-assessment processes are followed? We hope that greater transparency will help us better understand the current situation and allow us to contribute solutions using our expertise in service of national interests.”

Exclusive Report by the E-Commerce Association in Cooperation with ISPA

The latest results of a joint survey by the Internet and Infrastructure Commission and the ISPA Public Opinion Research Center, conducted in Khordad 1404 (June 2025), just days before the Israeli attack on Iran, show that among foreign social networks, Instagram is the most widely used platform in Iran.

Key findings:

- 86% of internet users use VPNs.

- Instagram is the first choice for 63% of internet users.

- 62.2% of users did not use VPNs or proxies before 1401 (2022), prior to the filtering of platforms such as Telegram and YouTube.

- 60% of those who use social networks as a source of income rely primarily on Instagram.

- 93.8% of Iranians under the age of 30 use VPNs.

Filtering and Tiered Internet: A Fundamental Policy Error

“Tiered internet”—referred to by policymakers as specialized access, differentiated access levels, or selective unblocking—is essentially an insistence on a flawed and repetitive policy cycle:

- Imposition of restrictive policies: The government imposes broad restrictions (e.g., filtering social networks) under the pretext of protecting citizens.

- Public resistance and side effects: Due to the irrationality and lack of public acceptance, people widely circumvent restrictions (VPN usage), creating new security, economic, and social problems.

- Symbolic solutions instead of real reform: Rather than revising the core policy, access is selectively restored for groups deemed more vocal (journalists, students, businesses).

Key Observations on Internet Quality in Iran

1. Continued Growth in Starlink Usage

The consumption of Starlink satellite internet continues to rise during 2024–2025.

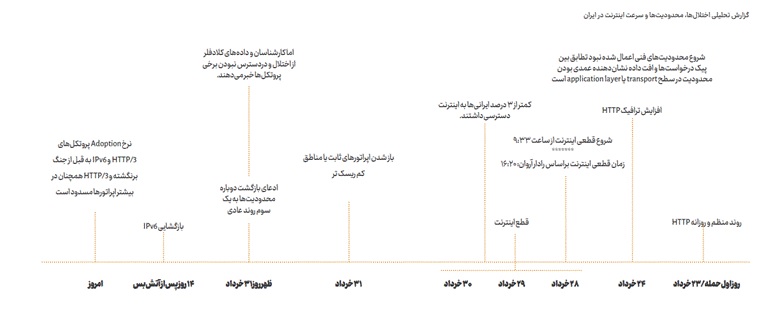

2. Disruptions Before and After the Israeli Attack

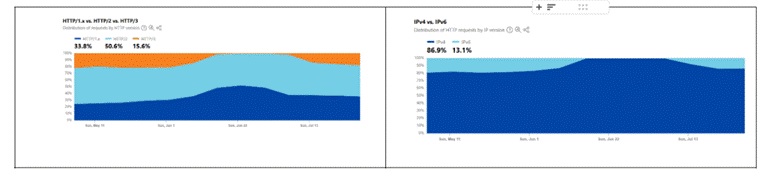

Previous reports highlighted the importance of HTTP/3 and how widespread disruptions to it impose significant costs and waste a major opportunity to improve internet quality. Current observations show that many disruptions recorded before the war persist even more than a month after the end of the attacks.

3. Slow Recovery of HTTP/3 and IPv6 Adoption

Adoption rates for HTTP/3 and IPv6 have not returned to pre-war levels, and HTTP/3 remains blocked by most operators.

4. Iran Among the Most Restricted Countries for Social Networks

Research shows that after Google Play and WhatsApp were unfiltered, international bandwidth usage increased by 10%. Officials have repeatedly stated that bandwidth supply is not a technical concern and that continued filtering is due to non-technical decisions by other authorities.

5. The “Iran Access” Policy Is as Ineffective as Filtering

Even more surprising than filtering foreign websites is restricting access to Iranian websites for users outside the country. Many government and banking websites are inaccessible internationally. Today, around 80% of Iranian government websites are Iran-access-only.

Recent cyberattacks on major financial systems—carried out via servers inside Iran—further demonstrate the futility of this policy, which imposes heavy costs without tangible benefits.

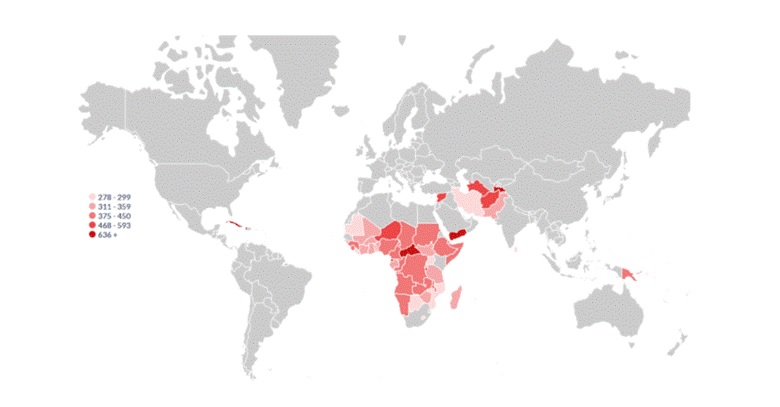

6. RTT Shows Iranian Internet Experience Resembles War-Torn and Underdeveloped Countries

Based on Round Trip Time (RTT) analysis, Iran’s internet user experience is worse than almost all countries except a few, including Cuba, Turkmenistan, Cameroon, Angola, Sudan, Congo, and Ethiopia.

With an average RTT of 295 milliseconds, Iran ranks alongside war-affected and least-developed countries.

In the introduction’s closing remarks, the report emphasizes that if consensus is to be achieved, it must first and foremost be with the people and their demands. Persisting stubbornly in maximum restrictions should be avoided. The clear public demand is free and high-speed internet for all Iranians, not tiered or privileged internet access for select groups.